Anthropology & Surveillance: Facial Recognition in the London Environment.

Facial recognition technology has gradually been rolled out across the capital, raising significant concern from human rights organisations and advocacy groups. Who are concerned about what they perceive to be untested and authoritarian technologies used to surveil the civilian population, unfairly targeting ethnic minority groups due to algorithmic bias. This project details the research methods I used to engage with this fieldsite and how Digital Anthropology can help us understand people's experiences of the London environment.

I set out to investigate what effect facial recognition technologies (FRT) have on London civilians by conducting ethnographic research with advocacy groups. With the intention of understanding how these digital technologies change the way we interact with the London environment, along with gauging societal attitudes to them, by observing civilian reactions and police responses.

The fieldsite for this project was rather unique as it comprised of the area surrounding the surveillance vans that the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) use to deploy their live facial recognition (LFR) cameras. This means that the area of study is something that was determined by the location of the technology rather than a rooted geographical location.

The LFR technology was being deployed in London Bridge, however, previous locations ranged from Westminster to Croydon. Future anthropological research of LFR technology could theoretically take place anywhere that law enforcement agencies deploy the technology.

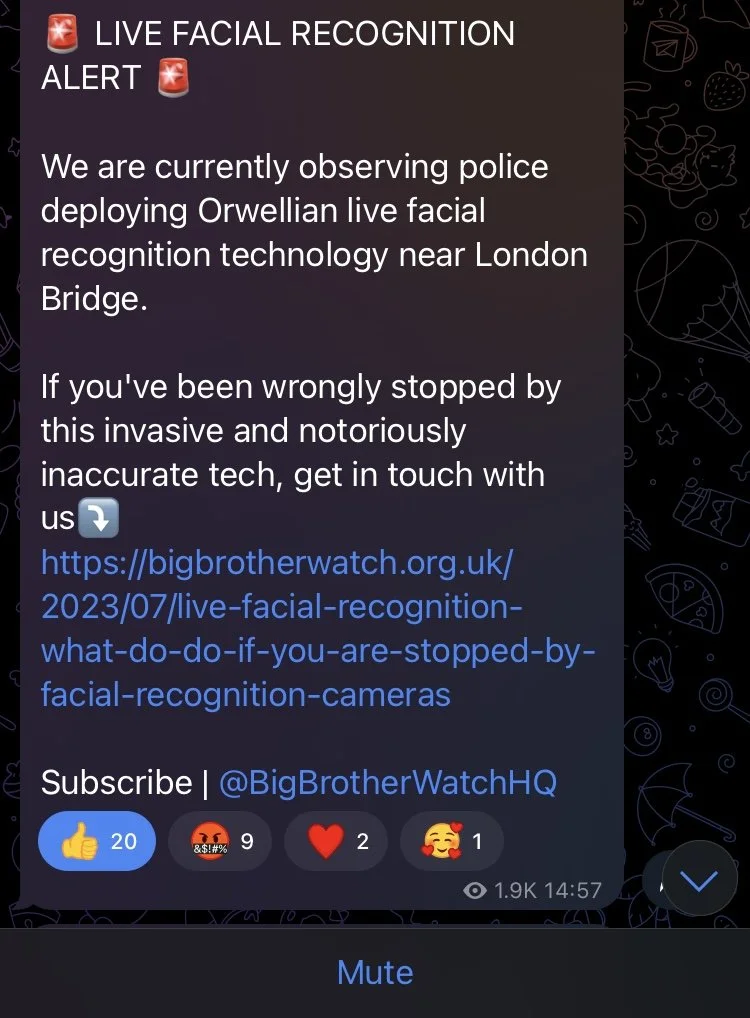

I conducted one offline participant observation of a LFR deployment in London Bridge and two interviews. I would not have been able to find the fieldsite without first observing the social media activity of both the police and campaigners. By subscribing to the Big Brother Watch newsletter and their telegram channel I could map where different deployments were taking place. What I noticed was that the LFR deployments were situated in a wider context of the UK government deploying digital technologies that infringe upon citizens' privacy, from digital ID’s to central bank digital currencies. All of which are receiving an increased amount of funding.

Big Brother Watch initially declined to partake in an interview for the project, however, they were more than happy to provide information about LFR rollouts which eventually led to me attending a deployment with two members of the organisation in London Bridge. I spent 4 hours at the fieldsite gathering qualitative data using my notebook and taking photos, both with my phone and a film camera. Which I then stored on Google Drive. During this period the police only stopped one black male who they let go after taking down some details, and a teenager who they deemed suspicious based on his behaviour rather than a match in their LFR system. Members from the Big Brother Watch team would then stand by and provide these individuals with information about the surveillance technology that had identified them.

In my search for organisations resisting surveillance technology I also came across Liberty, a human rights advocacy group seeking to make the UK a fairer place, comprised of lawyers, campaigners and policy experts. I got in touch with their office over the phone and managed to schedule an online interview with a policy and campaigns managers. We discussed the ethical implications of FRT and its tendency to display algorithmic bias along with other, non-tech based alternatives.

“The very first trials of facial recognition were at Notting Hill Carnival, which I think speaks volumes.”

“It’s all too easy for the for the government and the police to say these tools are neutral, when in actual fact, they embed and exacerbate a lot of racial discrimination.”

In order to understand how the London environment connected to a global trend of integrating surveillance technologies into law enforcement I also spoke with a Zurich based individual with experience working human face interaction in law enforcement who had attended an exhibition in Dubai showcasing technological developments in this field. Through discussing her research I learnt about alternative facial recognition techniques being trialled by the MPS that are less invasive and do not impose themselves on the London environment.

What this project ultimately shows us is that a vast majority of the public are unaware of the degree to which surveillance technologies are being deployed around the city, and that digital technologies are now becoming intrinsically linked to how citizens experience the London environment. It is only through the efforts of dedicated organisations that we become aware of these practices and the negative impacts they have on how members of minority communities are discriminated against. By utilising both online and offline methods my project demonstrates the value digital anthropology can bring in understanding how the environment can be turned into a site of surveillance. Unfairly targeting people of colour, whilst also eroding citizens' right to privacy by gathering biometric information against their will.